Traveling Through Nebraska's Great Plains Prairie Ecosystems

The Great Plains of North America, stretching across parts of Canada and the United States, encompass some of the most extensive and resilient ecosystems in the world. When traveling through Nebraska, it becomes apparent that the state's geographical makeup is predominantly composed of prairies. These ecosystems, classified as temperate grasslands, have been thriving for thousands of years, fostering diverse wildlife and unique plant species. Nebraska's location, bordered by the Missouri River to the east and the Rocky Mountains to the west, creates a divergent climate that greatly influences the characteristics of the prairies.

Nebraska's prairies can be divided into three main types: tallgrass, mixed-grass, and shortgrass. The tallgrass prairies are found primarily in the east, with examples like Pioneers Park in Lincoln, Nebraska. This area is dominated by big bluestem and switchgrass, with plants often reaching heights of six feet or more. The mixed-grass prairies, which cover a large portion of the state, are a transition zone between the tallgrass and shortgrass prairies, featuring a mix of grasses like little bluestem and sideoats grama. The shortgrass prairies, mainly found in western Nebraska, are typically found in drier areas, characterized by plants such as blue grama and buffalo grass.

One of the most significant factors contributing to the prairies' overall health is the periodic occurrence of fires, both natural and human-induced. For centuries, Native American tribes set fires to burn away dead vegetation, allowing new plant growth to emerge. This regular renewal maintains diversity in the ecosystem, creating an equilibrium between plant life, insect populations, and wildlife. Sites like the Oglala National Grassland near Chadron, Nebraska, demonstrate the evolution and dynamic nature of prairie ecosystems, as prescribed burns facilitate regeneration and resupply of vital nutrients.

A profound feature of the prairie ecosystem is the symbiotic relationship between specific plant species and the intricate network of fungi beneath them, known as mycorrhizal relationships. These mutually beneficial arrangements promote nutrient exchange and increase the resilience of the ecosystem as a whole. An exemplary model of such a relationship can be seen with the association of mycorrhizal fungi with big bluestem in the Konza Prairie Reserve, located near Manhattan, Kansas. This network functions by connecting different plant species, enhancing the resistance of grasses against pathogens, and ultimately bolstering the overall vitality of the prairie.

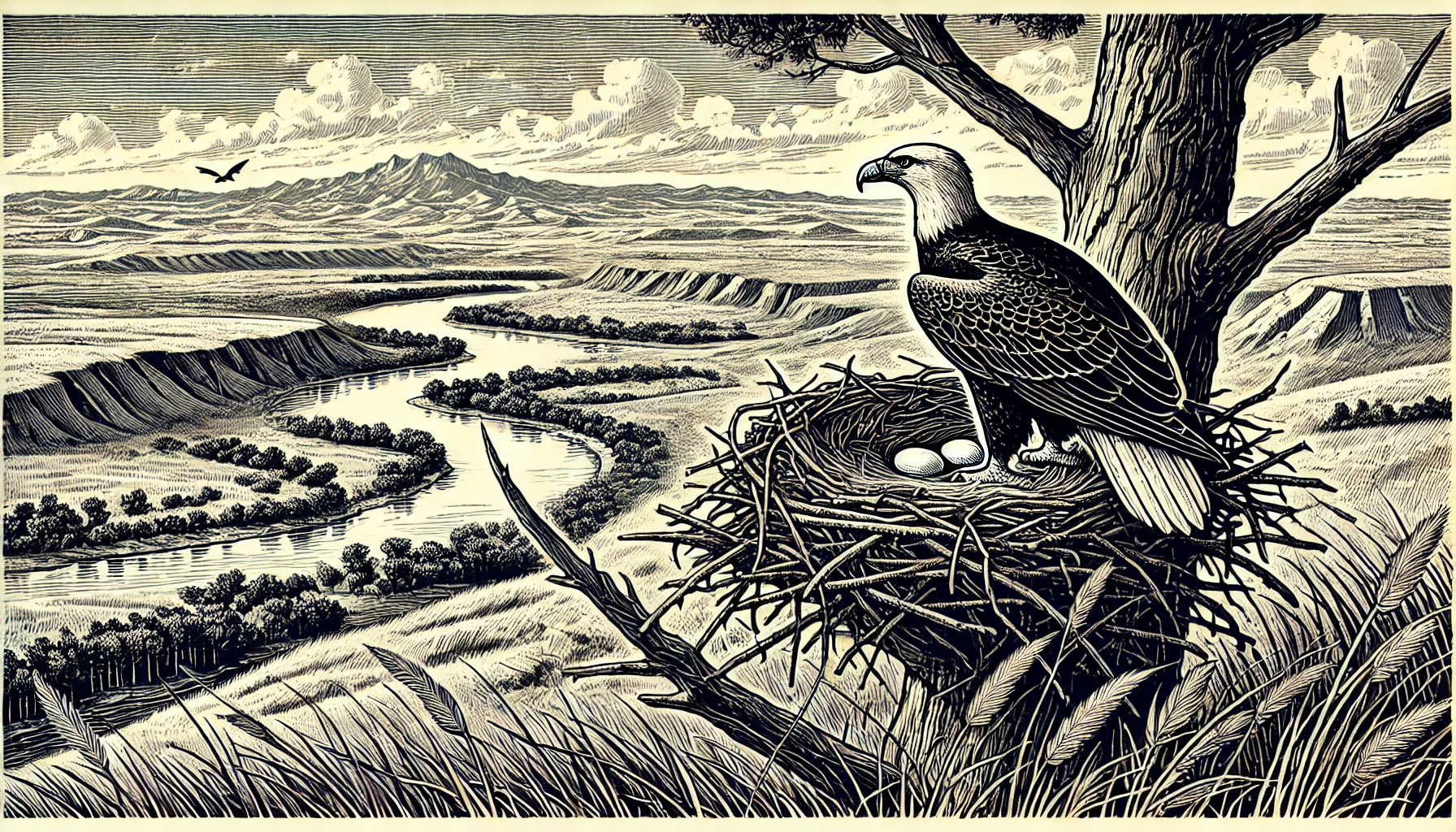

Prairies are also unique in their extensive wildlife presence, from diverse avian species such as the lark bunting, which nests exclusively on the prairies of the Great Plains, to the grassland-specific prey-predator dynamics between species such as the bobwhite quail and the short-eared owl. Observations of the local wildlife populations in wildlife refuges such as the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge, located near Ellsworth, Nebraska, illustrate the interwoven effects of prairie conservation on wildlife diversity and populations.

Another key aspect of prairie ecosystems is their susceptibility to adverse land-use changes, like agricultural operations and oil drilling, which may ultimately devastate native wildlife populations and drive out original plant species. However, recent adaptations in agricultural practices, such as integrating conservation tillage and shelterbelt ecology, as seen in areas like the Scotts Bluff National Monument in western Nebraska, promote a balance between prairie conservation and economic requirements.

Regardless of their strength and resilience, the sustainability of Nebraska's prairies relies heavily on continued responsible land management and human intervention. By developing and adapting conservation practices, much like the establishment of designated Nature Preserves within the Sandhills region, the timeless legacy of these natural treasures can be safeguarded for future generations to experience and appreciate.

Overall, Nebraska's Great Plains prairie ecosystems are intricate, vibrant worlds brimming with botanical and faunal diversity. By preserving and embracing this natural legacy, the state increases its resilience against environmental challenges and supports an incredibly unique component of North America's ecological makeup.

Nebraska's prairies can be divided into three main types: tallgrass, mixed-grass, and shortgrass. The tallgrass prairies are found primarily in the east, with examples like Pioneers Park in Lincoln, Nebraska. This area is dominated by big bluestem and switchgrass, with plants often reaching heights of six feet or more. The mixed-grass prairies, which cover a large portion of the state, are a transition zone between the tallgrass and shortgrass prairies, featuring a mix of grasses like little bluestem and sideoats grama. The shortgrass prairies, mainly found in western Nebraska, are typically found in drier areas, characterized by plants such as blue grama and buffalo grass.

One of the most significant factors contributing to the prairies' overall health is the periodic occurrence of fires, both natural and human-induced. For centuries, Native American tribes set fires to burn away dead vegetation, allowing new plant growth to emerge. This regular renewal maintains diversity in the ecosystem, creating an equilibrium between plant life, insect populations, and wildlife. Sites like the Oglala National Grassland near Chadron, Nebraska, demonstrate the evolution and dynamic nature of prairie ecosystems, as prescribed burns facilitate regeneration and resupply of vital nutrients.

A profound feature of the prairie ecosystem is the symbiotic relationship between specific plant species and the intricate network of fungi beneath them, known as mycorrhizal relationships. These mutually beneficial arrangements promote nutrient exchange and increase the resilience of the ecosystem as a whole. An exemplary model of such a relationship can be seen with the association of mycorrhizal fungi with big bluestem in the Konza Prairie Reserve, located near Manhattan, Kansas. This network functions by connecting different plant species, enhancing the resistance of grasses against pathogens, and ultimately bolstering the overall vitality of the prairie.

Prairies are also unique in their extensive wildlife presence, from diverse avian species such as the lark bunting, which nests exclusively on the prairies of the Great Plains, to the grassland-specific prey-predator dynamics between species such as the bobwhite quail and the short-eared owl. Observations of the local wildlife populations in wildlife refuges such as the Crescent Lake National Wildlife Refuge, located near Ellsworth, Nebraska, illustrate the interwoven effects of prairie conservation on wildlife diversity and populations.

Another key aspect of prairie ecosystems is their susceptibility to adverse land-use changes, like agricultural operations and oil drilling, which may ultimately devastate native wildlife populations and drive out original plant species. However, recent adaptations in agricultural practices, such as integrating conservation tillage and shelterbelt ecology, as seen in areas like the Scotts Bluff National Monument in western Nebraska, promote a balance between prairie conservation and economic requirements.

Regardless of their strength and resilience, the sustainability of Nebraska's prairies relies heavily on continued responsible land management and human intervention. By developing and adapting conservation practices, much like the establishment of designated Nature Preserves within the Sandhills region, the timeless legacy of these natural treasures can be safeguarded for future generations to experience and appreciate.

Overall, Nebraska's Great Plains prairie ecosystems are intricate, vibrant worlds brimming with botanical and faunal diversity. By preserving and embracing this natural legacy, the state increases its resilience against environmental challenges and supports an incredibly unique component of North America's ecological makeup.