Traveling the Transcontinental Railroad Through Nebraska

The Transcontinental Railroad, completed in 1869, was a groundbreaking feat of engineering that revolutionized the transportation landscape of the United States. Stretching from Omaha, Nebraska, to Sacramento, California, the railroad traversed the Great Plains, the Rocky Mountains, and the Sierra Nevada, providing a vital link between the east and west coasts. As part of the larger context of traveling through Nebraska, the Transcontinental Railroad holds significant historical importance in the development of the Cornhusker State.

Construction of the Transcontinental Railroad was overseen by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad, working in tandem to achieve the completion of the ambitious project. The Union Pacific, operating out of Omaha, was led by President Thomas C. Durant, who faced formidable challenges, including rugged terrain and hostile Sioux and Cheyenne tribes, in his quest to lay down the tracks. Meanwhile, the Central Pacific, building from California, was spearheaded by Theodore D. Judah, who designed the intricate tunnel system that enabled the railroad to cross the treacherous Sierra Nevada.

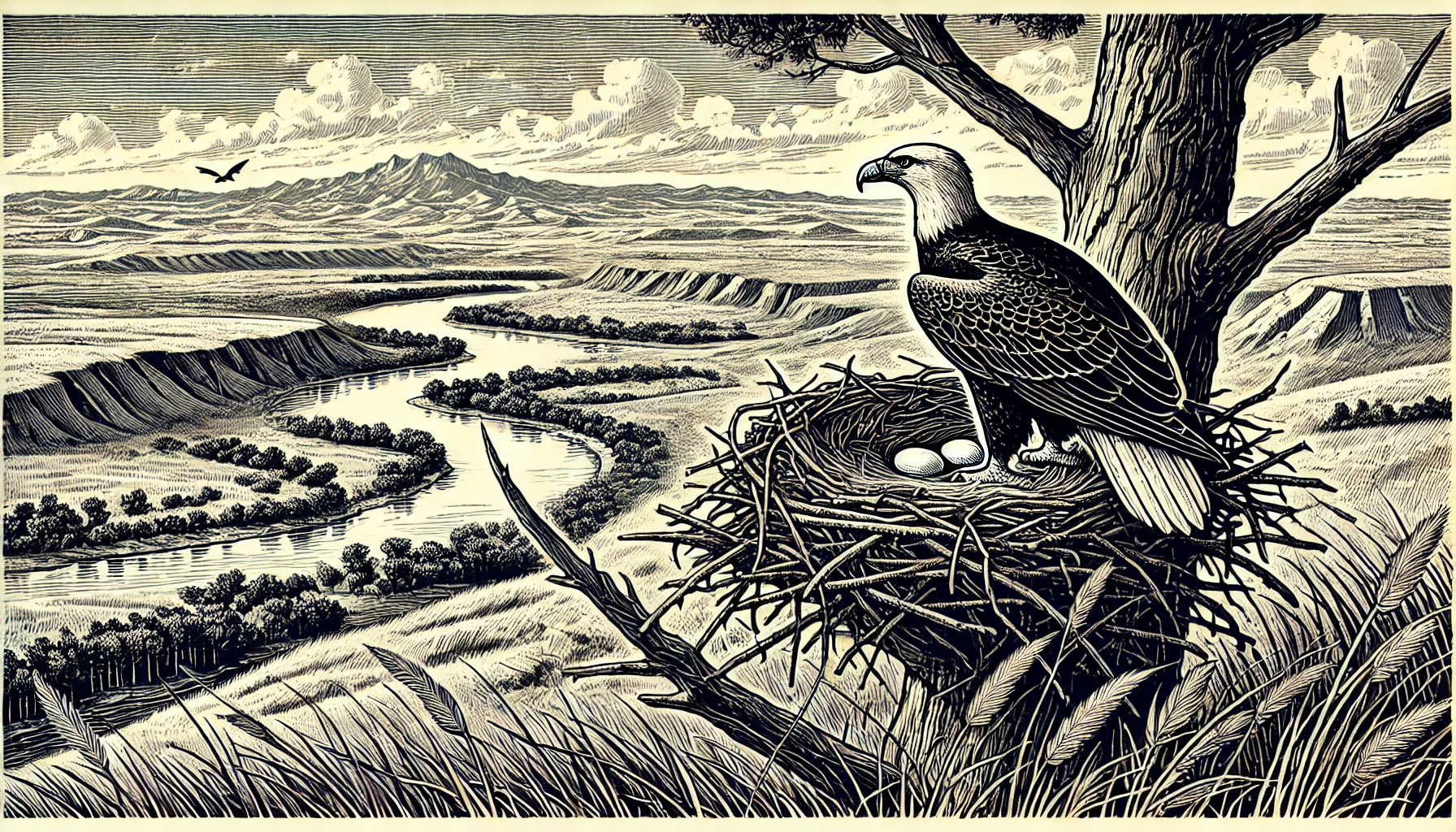

Nebraska was an integral component of the Transcontinental Railroad, with the Union Pacific construction team traversing the state from east to west. Key locations such as the Loup River Valley, Platte River, and Chimney Rock were crucial points along the route. Chimney Rock, located near present-day Bayard, served as an important landmark that marked the passing of the prairie and the transition to the rugged terrain of the Rocky Mountains. This geological formation stands 300 feet tall and was named by Father Pierre De Smet, who compared it to the organ pipes of a church organ.

Engineering feats were attained in constructing the Transcontinental Railroad, with notable structures including the Fort McPherson tunnel near Maxwell, which utilized innovative blasting techniques to create a tunnel through solid rock. Another impressive feat of engineering was the Dale Creek Toll Bridge, spanning 770 feet over its namesake creek near Cheyenne County. The Union Pacific's financial model innovatively involved the sale of construction supplies and provisions to workers to help pay off the construction costs.

Key towns such as Sidney and Ogallala, located along the Transcontinental Railroad route in Nebraska, originated as tent satellite towns or 'Hell on Wheels' towns, while crews worked on the tracks. Once the sections were finished and trains could be operated, many permanent towns and settlements emerged, enabling greater growth and economic development in these areas.

The role of immigrants who toiled in building the Transcontinental Railroad also holds significant importance, including thousands of skilled and hardworking workers, especially the Chinese laborers employed by the Central Pacific Railroad, and the labor force consisting of Irish, Mexican, and African Americans, toiling under harsh conditions for long hours, often in 72-hour shifts at pay rates commensurate to unskilled labor.

Not only did the Transcontinental Railroad have profound effects on the economy and demography of the U.S., but also was an impressive technological advancement, ultimately closing in late April 1869, with Stanford driving home the official 'Golden Spike' with a large wooden mallet at the terminus site in Promontory Summit near Ogden, Utah.

Upon the completion of the railroad, new population changes emerged within the continent as more settlers advanced to parts that had never been available for human habitation prior.

Construction of the Transcontinental Railroad was overseen by the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad, working in tandem to achieve the completion of the ambitious project. The Union Pacific, operating out of Omaha, was led by President Thomas C. Durant, who faced formidable challenges, including rugged terrain and hostile Sioux and Cheyenne tribes, in his quest to lay down the tracks. Meanwhile, the Central Pacific, building from California, was spearheaded by Theodore D. Judah, who designed the intricate tunnel system that enabled the railroad to cross the treacherous Sierra Nevada.

Nebraska was an integral component of the Transcontinental Railroad, with the Union Pacific construction team traversing the state from east to west. Key locations such as the Loup River Valley, Platte River, and Chimney Rock were crucial points along the route. Chimney Rock, located near present-day Bayard, served as an important landmark that marked the passing of the prairie and the transition to the rugged terrain of the Rocky Mountains. This geological formation stands 300 feet tall and was named by Father Pierre De Smet, who compared it to the organ pipes of a church organ.

Engineering feats were attained in constructing the Transcontinental Railroad, with notable structures including the Fort McPherson tunnel near Maxwell, which utilized innovative blasting techniques to create a tunnel through solid rock. Another impressive feat of engineering was the Dale Creek Toll Bridge, spanning 770 feet over its namesake creek near Cheyenne County. The Union Pacific's financial model innovatively involved the sale of construction supplies and provisions to workers to help pay off the construction costs.

Key towns such as Sidney and Ogallala, located along the Transcontinental Railroad route in Nebraska, originated as tent satellite towns or 'Hell on Wheels' towns, while crews worked on the tracks. Once the sections were finished and trains could be operated, many permanent towns and settlements emerged, enabling greater growth and economic development in these areas.

The role of immigrants who toiled in building the Transcontinental Railroad also holds significant importance, including thousands of skilled and hardworking workers, especially the Chinese laborers employed by the Central Pacific Railroad, and the labor force consisting of Irish, Mexican, and African Americans, toiling under harsh conditions for long hours, often in 72-hour shifts at pay rates commensurate to unskilled labor.

Not only did the Transcontinental Railroad have profound effects on the economy and demography of the U.S., but also was an impressive technological advancement, ultimately closing in late April 1869, with Stanford driving home the official 'Golden Spike' with a large wooden mallet at the terminus site in Promontory Summit near Ogden, Utah.

Upon the completion of the railroad, new population changes emerged within the continent as more settlers advanced to parts that had never been available for human habitation prior.