Warner Valley Farmers and Their Role in Nebraska History

Traveling through Nebraska, one cannot help but notice the vast expanses of agricultural land that dot the state's landscape. The story of Nebraska's farming history is complex and multifaceted, but one chapter worth exploring is that of the Warner Valley Farmers. Located near the town of Gering in Scotts Bluff County, the Warner Valley area was home to some of the state's earliest and most innovative farmers.

The Warner Valley Farmers' story began in the late 19th century, when the area was first settled by European-American pioneers. Many of these early settlers were German and Irish immigrants, who brought with them their knowledge of farming techniques and practices. One notable example is the establishment of the First Unitarian Church's charity farm in nearby Mitchell, which provided land and resources for struggling farmers. As the area grew in population and agricultural production, the Warner Valley Farmers began to form cooperatives and other organizations to promote their interests and share knowledge.

One notable organization that played a significant role in the history of Warner Valley Farmers was the Scotts Bluff County Farmers Institute. Founded in the late 19th century, the institute provided training and education for local farmers, as well as promoting innovation and experimentation in agricultural practices. Many notable Nebraska agricultural researchers, such as the University of Nebraska-Lincoln's Eugene Izett Robinson, gave lectures and presentations at the institute. Robinson, an expert on dryland farming, advocated for the use of fallow lands and crop rotation, techniques which eventually became widespread in the region.

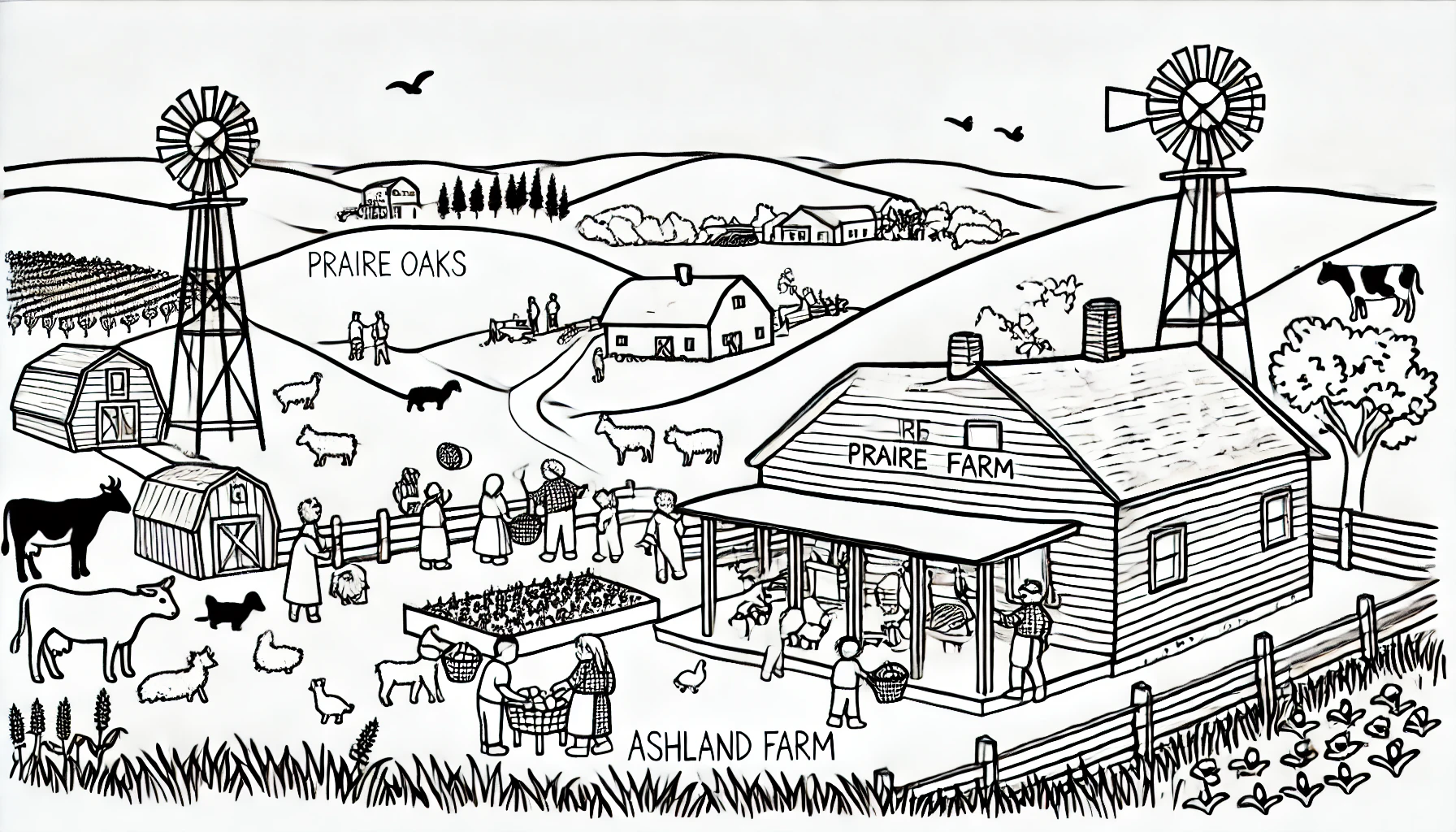

The Warner Valley Farmers' adoption of new techniques and technologies was also driven by the local soil conditions. The area's difficult topography and dry climate, caused by its proximity to the Sandhills region, made traditional farming techniques impractical. To adapt to these challenges, Warner Valley Farmers turned to irrigation systems and dryland farming methods. The use of windmills to pump water from the nearby Ogallala Aquifer, for example, allowed farmers to expand their arable lands and grow more drought-sensitive crops.

Throughout the 20th century, the Warner Valley Farmers continued to innovate and adapt to changing agricultural conditions. Many local farmers began to transition from dryland farming to more mechanized methods, driven by advances in technology and equipment. Today, the Warner Valley area remains a hub of agricultural activity, with many local farmers continuing to experiment with new techniques and technologies.

The Warner Valley Farmers' legacy can also be seen in the many historical sites and museums throughout the area. The Scotts Bluff National Monument, for example, commemorates the area's early history and pioneering spirit. The nearby Legacy of the Plains Museum in Gering showcases the region's agricultural history and the role of the Warner Valley Farmers in shaping the state's early development.

Despite their numerous contributions to Nebraska's history, the Warner Valley Farmers' story remains largely untold. Their legacy continues to shape the state's agricultural practices, however, and their innovative spirit remains a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of Nebraska's early farmers.

The Warner Valley Farmers' story began in the late 19th century, when the area was first settled by European-American pioneers. Many of these early settlers were German and Irish immigrants, who brought with them their knowledge of farming techniques and practices. One notable example is the establishment of the First Unitarian Church's charity farm in nearby Mitchell, which provided land and resources for struggling farmers. As the area grew in population and agricultural production, the Warner Valley Farmers began to form cooperatives and other organizations to promote their interests and share knowledge.

One notable organization that played a significant role in the history of Warner Valley Farmers was the Scotts Bluff County Farmers Institute. Founded in the late 19th century, the institute provided training and education for local farmers, as well as promoting innovation and experimentation in agricultural practices. Many notable Nebraska agricultural researchers, such as the University of Nebraska-Lincoln's Eugene Izett Robinson, gave lectures and presentations at the institute. Robinson, an expert on dryland farming, advocated for the use of fallow lands and crop rotation, techniques which eventually became widespread in the region.

The Warner Valley Farmers' adoption of new techniques and technologies was also driven by the local soil conditions. The area's difficult topography and dry climate, caused by its proximity to the Sandhills region, made traditional farming techniques impractical. To adapt to these challenges, Warner Valley Farmers turned to irrigation systems and dryland farming methods. The use of windmills to pump water from the nearby Ogallala Aquifer, for example, allowed farmers to expand their arable lands and grow more drought-sensitive crops.

Throughout the 20th century, the Warner Valley Farmers continued to innovate and adapt to changing agricultural conditions. Many local farmers began to transition from dryland farming to more mechanized methods, driven by advances in technology and equipment. Today, the Warner Valley area remains a hub of agricultural activity, with many local farmers continuing to experiment with new techniques and technologies.

The Warner Valley Farmers' legacy can also be seen in the many historical sites and museums throughout the area. The Scotts Bluff National Monument, for example, commemorates the area's early history and pioneering spirit. The nearby Legacy of the Plains Museum in Gering showcases the region's agricultural history and the role of the Warner Valley Farmers in shaping the state's early development.

Despite their numerous contributions to Nebraska's history, the Warner Valley Farmers' story remains largely untold. Their legacy continues to shape the state's agricultural practices, however, and their innovative spirit remains a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of Nebraska's early farmers.