Nebraska's Vanishing Water Table:

Hastening Concerns Beneath the Great Plains

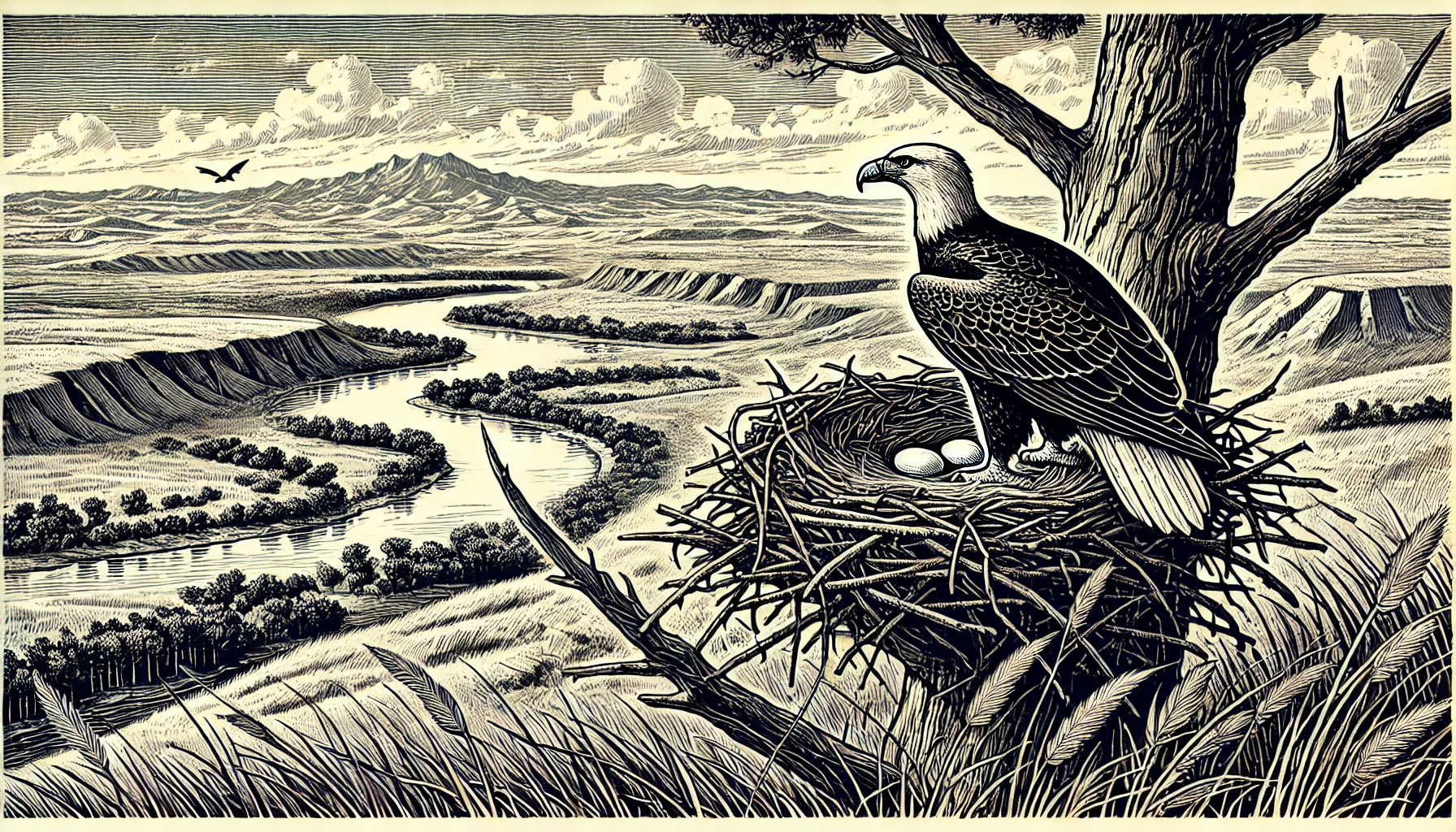

Traveling through Nebraska can be a feast for the senses, with rolling hills of tallgrass prairies and fields of ripening corn stretching towards the horizon. The Cornhusker State's rich agricultural heritage owes much of its success to a seemingly endless supply of groundwater from the High Plains Aquifer, also known as the Ogallala Aquifer. However, this vital water source is facing an unprecedented depletion that threatens the very foundations of the state's economy and food systems.

At the heart of the issue lies the mismatch between the rate of groundwater recharge and consumption. While the High Plains Aquifer recharges at a rate of about 2 inches per year, the rate of extraction has accelerated significantly due to the widespread adoption of center-pivot irrigation systems in the 1970s. In the Keith County area, situated near the town of Ogallala, water levels in the aquifer have declined by an astonishing 150 feet over the past 60 years. A study conducted by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln revealed that at this rate, 69% of the available groundwater could be depleted within the next 50 years.

The impact on local farmers has been palpable, as evidenced by the story of Randy Uhrmacher, a western Nebraska farmer who relies heavily on groundwater for his corn and soybean fields near the village of Trenton. In a 2018 interview with The New York Times, Uhrmacher recounted the drastic measures he had to take to keep his farm afloat, including spending $100,000 on a pipeline to access water from the adjacent Republican River basin. This decision was precipitated by the lack of available groundwater, forcing Uhrmacher to transition from a groundwater-based irrigation system to a more expensive and energy-intensive process.

The ripple effects of aquifer depletion extend far beyond the agricultural sector, affecting local communities that rely on the aquifer for drinking water. In the small town of Alliance, located in the Sandhills region of north-central Nebraska, residents have reported taste and odor changes in their municipal water supply due to increasing levels of naturally occurring radionuclides and other mineral contaminants. As the water table continues to decline, concerns about the long-term sustainability of these water sources intensify.

The data suggests that replenishment of the aquifer through natural recharge is not sufficient to balance the current consumption rates. Scientists point to the need for more efficient irrigation practices and regulations to curb groundwater over-extraction. Consequently, policymakers and researchers have been working together to develop more water-efficient technologies and promote water conservation practices among farmers.

Recent efforts by the Nebraska Natural Resources Commission to implement water conservation measures are pointing towards a more sustainable future for the state's agricultural industry. This includes initiatives such as weather-based irrigation management and soil moisture monitoring programs. Additionally, innovative ideas like drip irrigation systems and subsurface drip irrigation are being piloted in areas with limited water availability.

The consequences of inaction on this pressing issue can be dire for Nebraska's economy and food systems. Immediate attention and policy adjustments aimed at preserving the High Plains Aquifer are essential to mitigate these risks and ensure the long-term sustainability of the Cornhusker State's agricultural sector.

Traveling through Nebraska can be a feast for the senses, with rolling hills of tallgrass prairies and fields of ripening corn stretching towards the horizon. The Cornhusker State's rich agricultural heritage owes much of its success to a seemingly endless supply of groundwater from the High Plains Aquifer, also known as the Ogallala Aquifer. However, this vital water source is facing an unprecedented depletion that threatens the very foundations of the state's economy and food systems.

At the heart of the issue lies the mismatch between the rate of groundwater recharge and consumption. While the High Plains Aquifer recharges at a rate of about 2 inches per year, the rate of extraction has accelerated significantly due to the widespread adoption of center-pivot irrigation systems in the 1970s. In the Keith County area, situated near the town of Ogallala, water levels in the aquifer have declined by an astonishing 150 feet over the past 60 years. A study conducted by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln revealed that at this rate, 69% of the available groundwater could be depleted within the next 50 years.

The impact on local farmers has been palpable, as evidenced by the story of Randy Uhrmacher, a western Nebraska farmer who relies heavily on groundwater for his corn and soybean fields near the village of Trenton. In a 2018 interview with The New York Times, Uhrmacher recounted the drastic measures he had to take to keep his farm afloat, including spending $100,000 on a pipeline to access water from the adjacent Republican River basin. This decision was precipitated by the lack of available groundwater, forcing Uhrmacher to transition from a groundwater-based irrigation system to a more expensive and energy-intensive process.

The ripple effects of aquifer depletion extend far beyond the agricultural sector, affecting local communities that rely on the aquifer for drinking water. In the small town of Alliance, located in the Sandhills region of north-central Nebraska, residents have reported taste and odor changes in their municipal water supply due to increasing levels of naturally occurring radionuclides and other mineral contaminants. As the water table continues to decline, concerns about the long-term sustainability of these water sources intensify.

The data suggests that replenishment of the aquifer through natural recharge is not sufficient to balance the current consumption rates. Scientists point to the need for more efficient irrigation practices and regulations to curb groundwater over-extraction. Consequently, policymakers and researchers have been working together to develop more water-efficient technologies and promote water conservation practices among farmers.

Recent efforts by the Nebraska Natural Resources Commission to implement water conservation measures are pointing towards a more sustainable future for the state's agricultural industry. This includes initiatives such as weather-based irrigation management and soil moisture monitoring programs. Additionally, innovative ideas like drip irrigation systems and subsurface drip irrigation are being piloted in areas with limited water availability.

The consequences of inaction on this pressing issue can be dire for Nebraska's economy and food systems. Immediate attention and policy adjustments aimed at preserving the High Plains Aquifer are essential to mitigate these risks and ensure the long-term sustainability of the Cornhusker State's agricultural sector.