African American Settlements in the Great Plains: A Legacy of Resilience and Determination

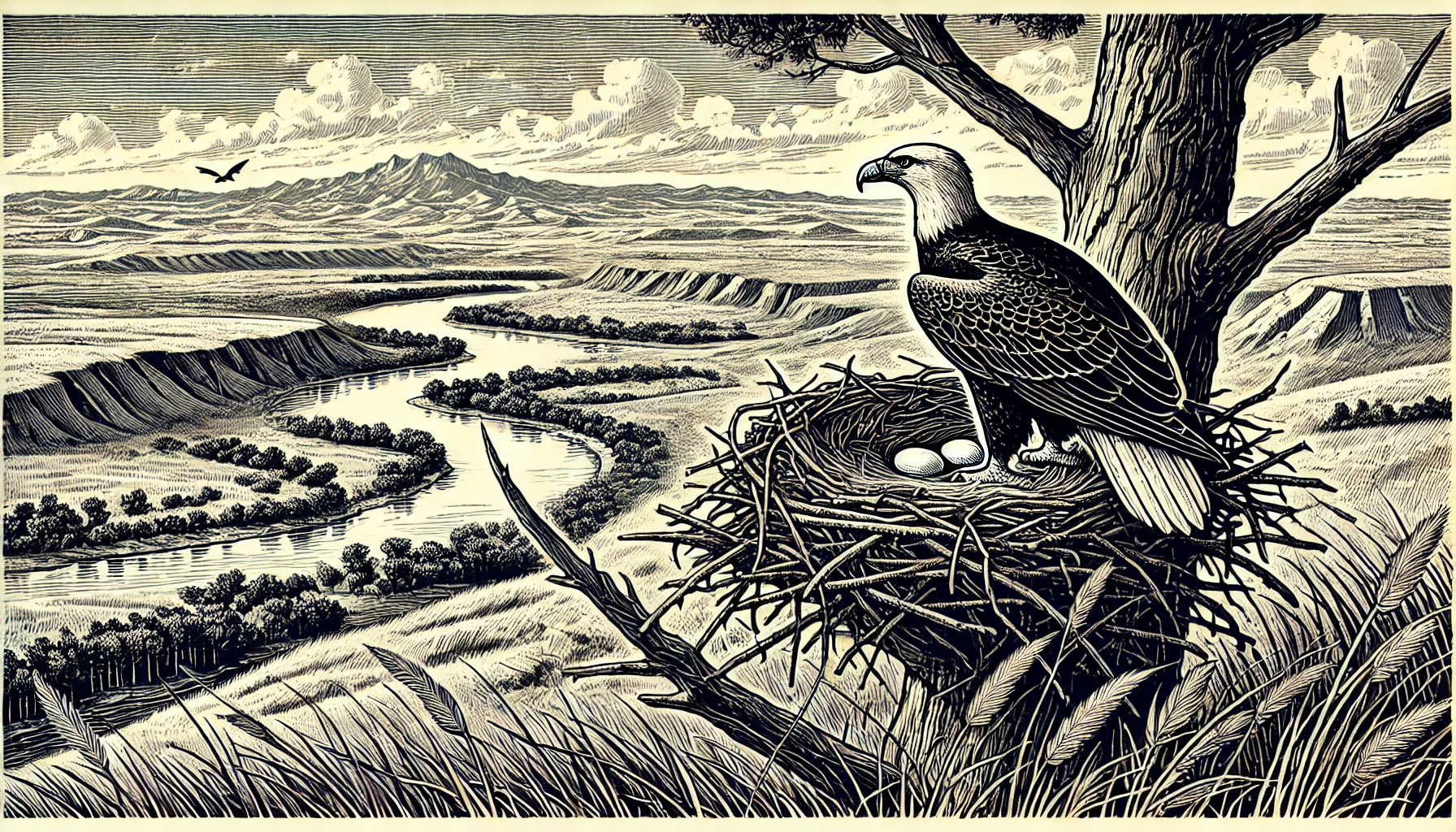

Traveling through Nebraska, one often encounters sparse landscapes and rural communities that have endured the harsh elements of the Great Plains. Amidst these rolling hills and vast open spaces, lies a lesser-known aspect of American history – the African American settlements that once thrived in this region. Along the trails and byways of Nebraska, remnants of these settlements evoke a deeper exploration into the experiences of African American homesteaders who established lives and communities amidst the challenges of the Great Plains.

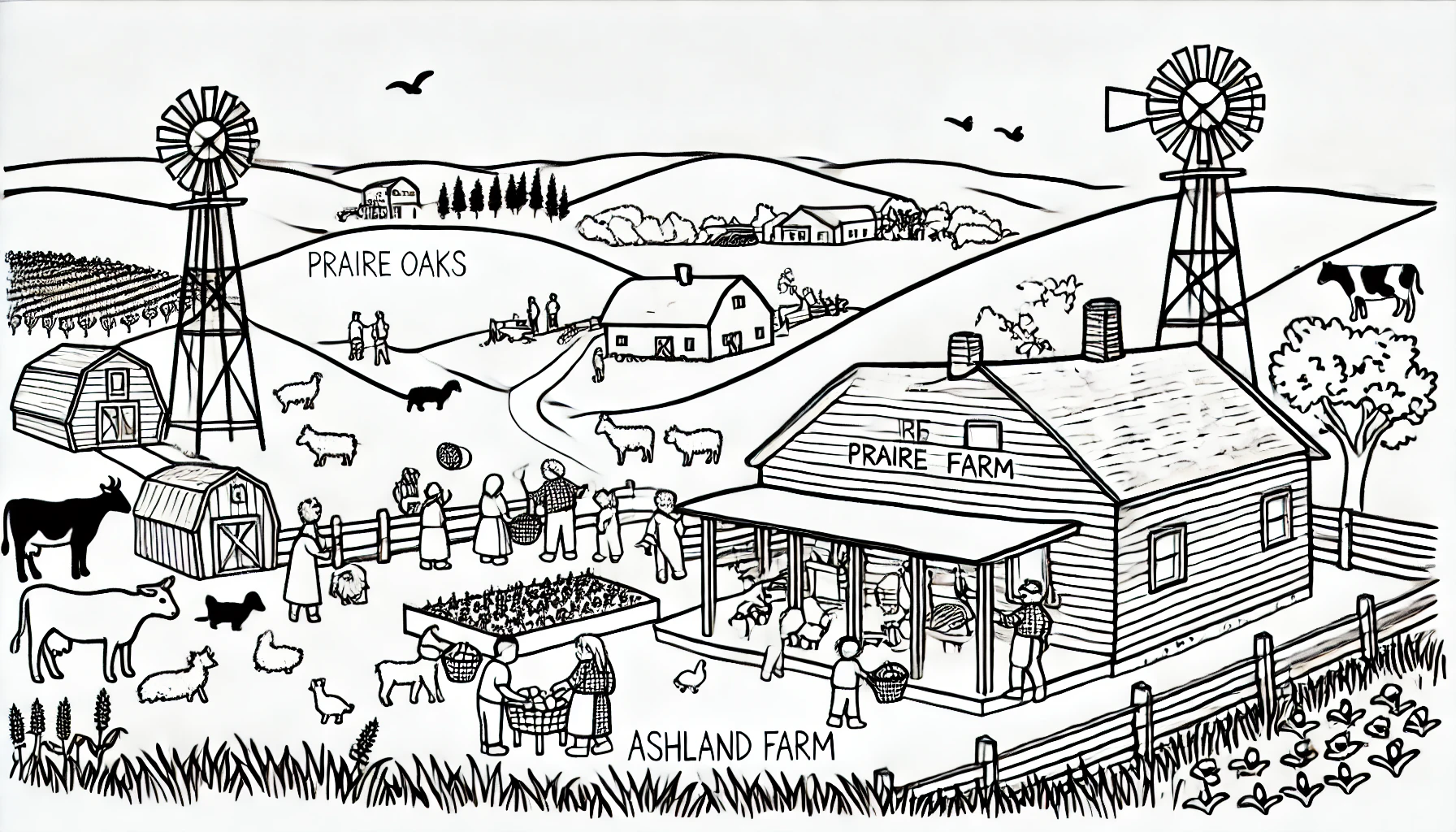

One such settlement, the community of DeWitty, located near the town of Brownlee in Cherry County, Nebraska, emerged in the late 19th century as a prominent example of African American pioneering and resilience. Founded by two groups of Black settlers, one from Mississippi and the other from Alabama, the community boasted over 60 households and persisted for nearly 40 years. Although the settlement dissolved by 1910, remnants of DeWitty remain, such as the preserved site of the former community schoolhouse. This cultural artifact stands as a testament to the community's efforts to build a better life for themselves in the face of challenging circumstances.

The Homestead Act of 1862 played a significant role in facilitating these African American settlements, particularly in Nebraska. By offering 160 acres of land for a small filing fee, African Americans saw an opportunity to own land, break free from the shackles of post-Civil War sharecropping, and establish a sense of social and economic security. Within the vast lands of the Great Plains, places like Valley County, where DeWitty was established, presented attractive options for settlement due to the fertile soil and ample grazing land for livestock.

However, the harsh realities of the Great Plains environment also proved challenging for these settlements. Harsh weather conditions, coupled with thin soil, made it difficult to maintain a stable agricultural foundation. Families often turned to diverse ways of making a living, including hunting, gathering, and trading with neighboring communities. In addition, the communities relied on informal networks of shared knowledge and kinship to navigate these challenges, such as swapping supplies, tools, and advice on weathering storms.

Life in the settlements also reflected broader social changes during this period. In many cases, the homestead communities offered an escape from the entrenched racial segregation prevalent in urban settings. However, as the communities interacted with neighboring towns and institutions, settlers still encountered elements of racism and hostility, such as limited access to education and healthcare.

When examining the experiences of African American settlers in Nebraska, it becomes evident that historical remnants of their presence are primarily relegated to the silence of historical memory or the subtle markers that dot the Nebraska landscape. Amidst these vast expanses of open space and rural communities, it is essential to uncover the significance of these pioneering settlements, understanding their place within the broader narrative of American history and acknowledging the challenges and triumphs they faced along the way.

Further exploration along the trails and byways of Nebraska reveals additional examples of African American settlements, each offering its own unique perspective on the region's complex social history. From Langston, Oklahoma, to Nicodemus, Kansas, the remnants of these communities weave an intricate tapestry of experiences and stories of the African American pioneers who defied the odds to make their mark on the Great Plains.

In conjunction with the findings from DeWitty, it is also crucial to pay homage to these communities, acknowledging the long-lasting cultural significance that have come to define the rich and varied history of the Great Plains, and inspire greater investigation into this lesser-known chapter of American history.

One such settlement, the community of DeWitty, located near the town of Brownlee in Cherry County, Nebraska, emerged in the late 19th century as a prominent example of African American pioneering and resilience. Founded by two groups of Black settlers, one from Mississippi and the other from Alabama, the community boasted over 60 households and persisted for nearly 40 years. Although the settlement dissolved by 1910, remnants of DeWitty remain, such as the preserved site of the former community schoolhouse. This cultural artifact stands as a testament to the community's efforts to build a better life for themselves in the face of challenging circumstances.

The Homestead Act of 1862 played a significant role in facilitating these African American settlements, particularly in Nebraska. By offering 160 acres of land for a small filing fee, African Americans saw an opportunity to own land, break free from the shackles of post-Civil War sharecropping, and establish a sense of social and economic security. Within the vast lands of the Great Plains, places like Valley County, where DeWitty was established, presented attractive options for settlement due to the fertile soil and ample grazing land for livestock.

However, the harsh realities of the Great Plains environment also proved challenging for these settlements. Harsh weather conditions, coupled with thin soil, made it difficult to maintain a stable agricultural foundation. Families often turned to diverse ways of making a living, including hunting, gathering, and trading with neighboring communities. In addition, the communities relied on informal networks of shared knowledge and kinship to navigate these challenges, such as swapping supplies, tools, and advice on weathering storms.

Life in the settlements also reflected broader social changes during this period. In many cases, the homestead communities offered an escape from the entrenched racial segregation prevalent in urban settings. However, as the communities interacted with neighboring towns and institutions, settlers still encountered elements of racism and hostility, such as limited access to education and healthcare.

When examining the experiences of African American settlers in Nebraska, it becomes evident that historical remnants of their presence are primarily relegated to the silence of historical memory or the subtle markers that dot the Nebraska landscape. Amidst these vast expanses of open space and rural communities, it is essential to uncover the significance of these pioneering settlements, understanding their place within the broader narrative of American history and acknowledging the challenges and triumphs they faced along the way.

Further exploration along the trails and byways of Nebraska reveals additional examples of African American settlements, each offering its own unique perspective on the region's complex social history. From Langston, Oklahoma, to Nicodemus, Kansas, the remnants of these communities weave an intricate tapestry of experiences and stories of the African American pioneers who defied the odds to make their mark on the Great Plains.

In conjunction with the findings from DeWitty, it is also crucial to pay homage to these communities, acknowledging the long-lasting cultural significance that have come to define the rich and varied history of the Great Plains, and inspire greater investigation into this lesser-known chapter of American history.