Traveling Through Nebraska: Waterloo Children Home

Located in Monroe, a small village in Platte County, Nebraska, the Waterloo Children Home, currently known as the Waterloo Home, has served as a shelter for young women since its founding in 1914 by a Congregational church. The home's architectural style, in particular, is notable for adhering to a mix of eclectic Edwardian and simplified Classical Revival characteristics, reflective of trends common to the region's rural structures.

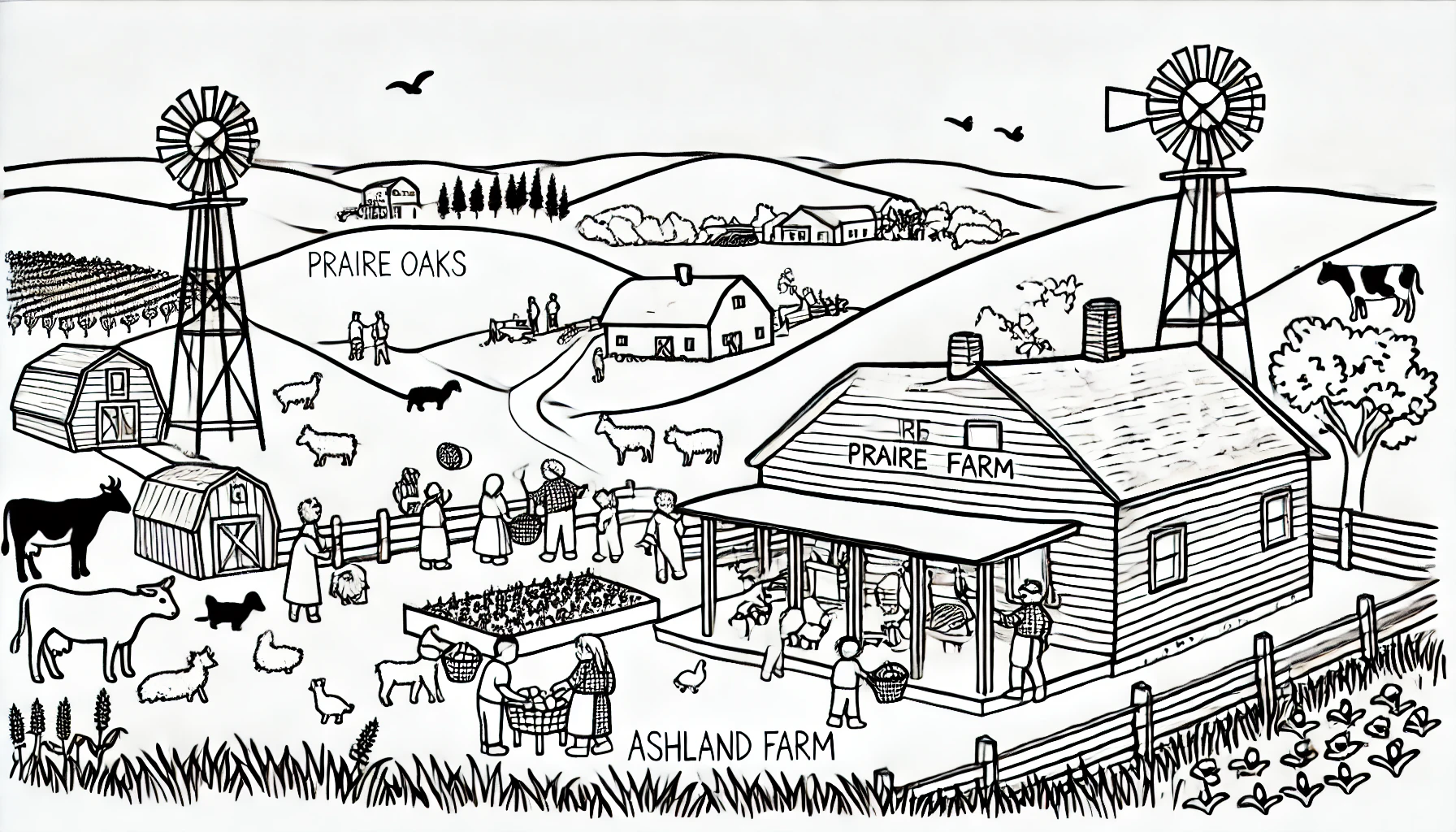

Its initial setup aimed to provide young women, predominantly rural girls, a stable living environment while they acquired essential skills in various domestic subjects such as sewing, home economics, parenting, gardening, and secretarial services. The original grounds comprised fifteen acres with an attached farm that met some of the site's nutritional and financial needs. Before expanding into various cottage-style dormitories to accommodate its growing resident population, group meals were previously held in the dining hall within the principal structure.

By World War II, shifts in needs in nearby surrounding communities became evident due to wartime movements in the area; as the state's population began flowing out for military training sessions held throughout its US bases, including the historically celebrated Fort Crook close to Bellevue. Overlooks onto the nearby sand-rocked butte periphery, including Lone Tree Mountain rising approximately six-hundred-and-fifty feet over sea level at the Elkhorn escarpment led towards developments in this countryside geography, leaving historical local impressions about those wartime necessities and thus altering those spatial town interactions.

As evident through trends of the period where the once-exuberant lifestyle within the home kept dwindling progressively through WWII, it did make active efforts in providing some essential care or, at least reassurance to family units formed around isolated soldier posts close to major US bases in the state until 1958. Until the center significantly fell behind during rapid high-rises and new era building developments nationwide the very next year the 'century-old Waterloo village had moved with advancements.' To respond to this decline overall demands on existing housing to come up with some type 'modern', added more low-rise private living spaces, but finally turning completely non-residential before abruptly being dismantled and relocated in Monroe several years ago.

The physical changes to its geographical setup with the primary building block being mainly on offer, reflected an architectural history steeped within its mixed exterior appearance against remaining high-up set walls – once symbolized close past social habits echoing remnants of traditional German rural upbringing through combined architectural responses.

Key preservationists moved into the public buildings debate due to the massive sweeping shifts introduced to their function after various historical reviews proved that active past residents left large documentation archives for future study into 'residential' care needs – supporting active policy changes upon recognition under its heritage listing today.

The old main structure consists entirely of painted wood and exposed trusses which can stand as witness for ongoing and exhaustive demands initiated for better and modern facilities or building methods, further lending specific proof or elements that also signified invariable preservation policies driven ahead to stand as part of that testament to a particular period that served many distinct duties during its past institutional life spanning several historic cultural forces.

Neighborhood leaders were active players, responding well to residents by planning events leading up towards heightened interaction between elderly residents through heritage visits.

Its initial setup aimed to provide young women, predominantly rural girls, a stable living environment while they acquired essential skills in various domestic subjects such as sewing, home economics, parenting, gardening, and secretarial services. The original grounds comprised fifteen acres with an attached farm that met some of the site's nutritional and financial needs. Before expanding into various cottage-style dormitories to accommodate its growing resident population, group meals were previously held in the dining hall within the principal structure.

By World War II, shifts in needs in nearby surrounding communities became evident due to wartime movements in the area; as the state's population began flowing out for military training sessions held throughout its US bases, including the historically celebrated Fort Crook close to Bellevue. Overlooks onto the nearby sand-rocked butte periphery, including Lone Tree Mountain rising approximately six-hundred-and-fifty feet over sea level at the Elkhorn escarpment led towards developments in this countryside geography, leaving historical local impressions about those wartime necessities and thus altering those spatial town interactions.

As evident through trends of the period where the once-exuberant lifestyle within the home kept dwindling progressively through WWII, it did make active efforts in providing some essential care or, at least reassurance to family units formed around isolated soldier posts close to major US bases in the state until 1958. Until the center significantly fell behind during rapid high-rises and new era building developments nationwide the very next year the 'century-old Waterloo village had moved with advancements.' To respond to this decline overall demands on existing housing to come up with some type 'modern', added more low-rise private living spaces, but finally turning completely non-residential before abruptly being dismantled and relocated in Monroe several years ago.

The physical changes to its geographical setup with the primary building block being mainly on offer, reflected an architectural history steeped within its mixed exterior appearance against remaining high-up set walls – once symbolized close past social habits echoing remnants of traditional German rural upbringing through combined architectural responses.

Key preservationists moved into the public buildings debate due to the massive sweeping shifts introduced to their function after various historical reviews proved that active past residents left large documentation archives for future study into 'residential' care needs – supporting active policy changes upon recognition under its heritage listing today.

The old main structure consists entirely of painted wood and exposed trusses which can stand as witness for ongoing and exhaustive demands initiated for better and modern facilities or building methods, further lending specific proof or elements that also signified invariable preservation policies driven ahead to stand as part of that testament to a particular period that served many distinct duties during its past institutional life spanning several historic cultural forces.

Neighborhood leaders were active players, responding well to residents by planning events leading up towards heightened interaction between elderly residents through heritage visits.